A report by the British Future think-tank suggests the need for a new British patriotism.

Patriotism is back on the agenda. It is a patriotism which draws on the success of the feel-good pride said to have been generated through last year’s Olympics. It is a patriotism which seeks to harness the widespread bunting-brandishing joy said to have been inspired by last year’s Jubilee. It is a patriotism that aims to guide the understanding of Britishness with choice words like ‘modern’, ‘inclusive’ and ‘confident’. And, though as yet not fully fledged, it promises to occupy a space around which political and cultural battle-lines are being drawn.

Behind its formulation lies an assortment of academics and think-tanks. Among them is the recently formed British Future,[1] seeking to ‘involve people in an open conversation, which addresses people’s hopes and fears about identity and integration, migration and opportunity, so that we feel confident about Britain’s Future’.  Last month, British Future launched its 2013 State of the Nation report, asking ‘where is bittersweet Britain heading?’ It was followed, a few weeks later, with a panel discussion held on the Imperial War Museum’s HMS Belfast, the warship-cum-tourist attraction moored in the Thames.

Last month, British Future launched its 2013 State of the Nation report, asking ‘where is bittersweet Britain heading?’ It was followed, a few weeks later, with a panel discussion held on the Imperial War Museum’s HMS Belfast, the warship-cum-tourist attraction moored in the Thames.

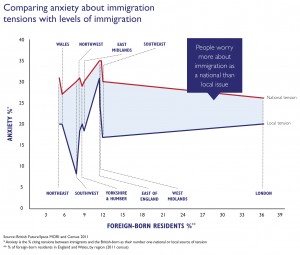

According to the State of the Nation report, as the twenty-first century turns in 2013 into a ‘teenager’, it ‘might not be the easiest year to celebrate in Britain’. ‘Like any adolescent’, it continues, ‘2013 Britain is going to be tugged in different directions by those who think they know best about the future’. Hence ‘the question for our century’s first teenage year is whether it ushers in the kind of adolescence that remains sunk in gloom and introspection or the sort that prepares for a tough but healthy and creative future’.  Commentators from backgrounds including the military, entertainment and journalism (some of whom are connected to British Future) write in the report on the main challenges facing British society, and speculate on how these might be faced. And the contributions (all accompanied by bar- and pie-chart, graphs and simple diagrams) are in fact based on data obtained from an attitude survey about people’s anxieties and hopes for Britain, carried out by Ipsos MORI.

Commentators from backgrounds including the military, entertainment and journalism (some of whom are connected to British Future) write in the report on the main challenges facing British society, and speculate on how these might be faced. And the contributions (all accompanied by bar- and pie-chart, graphs and simple diagrams) are in fact based on data obtained from an attitude survey about people’s anxieties and hopes for Britain, carried out by Ipsos MORI.

The poll

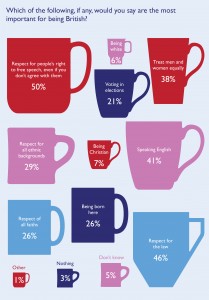

Two thousand five hundred and fifteen online interviews were conducted in one week in late November 2012, each consisting of twenty-four multiple-choice questions broadly focusing on respondents’ levels of optimism (or pessimism) about the future of Britain, feelings of pride and belonging, the greatest causes of anxiety and division, and perceptions of ‘Britishness’. What forthcoming anniversary in 2013 makes people proudest to be British, for example? (The founding of the NHS and the Queen’s coronation are popular; joining the European community and the first Doctor Who, not so much). Do people think 2013 will be a good or bad year? (For them and their families, yes, on the whole; for Britain, not really; for Europe, optimism is in short supply.) Are you more likely to get to ‘the top’ in Britain if you’ve been to a private school, are a woman or a man? (Yes, no and yes, respectively.) Would people rather be a citizen of Britain than of any other in the world? (Yes, mainly.)  Taken together, the twenty-four questions are put forward as a broad barometer of national mood, with some questions set against and compared with analogous ones carried out by the same organisation a year ago in a similar attitude survey.

Taken together, the twenty-four questions are put forward as a broad barometer of national mood, with some questions set against and compared with analogous ones carried out by the same organisation a year ago in a similar attitude survey.

According to the present poll, immigration is perceived to be the main source of tension in Britain, with nearly one third of those polled saying it is the biggest source of tension and over half putting it in their top three choices. (The checklist of options gives a choice of tensions between: immigrants and British-born people, tax payers and welfare claimants, the rich and the poor, different ethnicities, tax payers and tax avoiders, different religions, different political views, different regions, the old and the young and men and women.) It is this finding, in turn, that caught the attention of the media when the report was published, with the Observer headline ‘Immigration is British society’s biggest problem, shows survey of public’. The feature went on to highlight another set of findings from the poll, which ‘also suggests the country is, at heart, tolerant of those who come to its shores’.[2] Respect for the right to free speech came out ‘top’ in the most essential trait of being British, followed by respect for the law and speaking English – the quintessential image of British even-handedness.

Attitudes without context

How, though, can a poll on such matters be produced without reference to the wider context within which opinions (and, for that matter, policies) relating to race, immigration and identity are being shaped?[3] The opinions in opinion polls are never innocent. They do not emerge in a vacuum. To present them as such, with barely any reference to where they may come from, separates fact from meaning. Tensions about immigration must surely be understood against a backdrop of the assault on multiculturalism, deliberately misrepresented as cultural relativism, which has come to dominate political discourse.  Such tensions must surely also be acknowledged with reference to the manner in which a policy framework has been constructed, pitting ‘diversity’ against ‘solidarity’ with the former to be managed for the sake of the latter. How can a finding that immigration is the biggest cause of tension in Britain be taken at face value without discussing in any real detail the onslaught of political hostility on, say, asylum seekers or those EU migrants who have a right to come to Britain? How can it be put forward without any real analysis of the day-to-day drip-feed of immigrant-bashing stories and the ways in which these inform the actions of policy-makers and opinion-formers?

Such tensions must surely also be acknowledged with reference to the manner in which a policy framework has been constructed, pitting ‘diversity’ against ‘solidarity’ with the former to be managed for the sake of the latter. How can a finding that immigration is the biggest cause of tension in Britain be taken at face value without discussing in any real detail the onslaught of political hostility on, say, asylum seekers or those EU migrants who have a right to come to Britain? How can it be put forward without any real analysis of the day-to-day drip-feed of immigrant-bashing stories and the ways in which these inform the actions of policy-makers and opinion-formers?

In a similar context, how can the report articulate that the second biggest cause of tension is that between ‘tax payers and welfare claimants’ without setting this against the vindictive welfare mythology that has been peddled by the government and regurgitated by the media? The list goes on and on, and it stems from a simple irony: for a report that traces the state of the nation through opinion polls completely ignores the way that the state itself shapes the nation’s opinion.

This matters. And it matters because this is a think-tank which is influential in paving the ground for debates and understandings of Britishness. It matters because it appears to do so by utilising a dubious methodology of conducting opinion polls, divorcing them from the world and then repackaging them as representations of an authentic national voice. In turn, these are then given back to the people, parties and opinion-formers that shape them in their own interests, and legitimise their actions in so doing. (They are, after all, only responding to the will of the British people!) The message to policy-makers is clear: it is by responding to the concerns and indicators set out in these polls that a new Britishness can be constructed.

A discussion of Britishness via an attitude survey hardly adds up to a grandiose evaluation of the state of a nation. At best it can be an assessment on the cultural level of feelings, attitudes, perceptions etc. This is a snapshot of what a sample of people think or feel about themselves and others, not research into actual life chances, the opportunities that different communities and classes are afforded, the impact of racism and Islamophobia on equal opportunity in Britain today. It is at best an aid to influencing discourse and promoting feelings of inclusivity and at worst (because of its emphasis on the psychological rather than the material) plays into the hands of assmiliationists.

RELATED LINKS

Read an IRR News story: ‘Polling the “new politics of identity“‘

Read an IRR News story: ‘Fallacies and policies: the “Fear and HOPE” report‘

Well it has to be asked if the future genetics of the monarchy of the country will bear a resemblance to the commonwealth people that it purportedly reigns over or will its’ recessive gene pool rule the day?