Below we reproduce a review of a new exhibition, ‘No Colour Bar’, which was previously published in The Voice.

A new exhibition breathes life into a story of struggle and activism that is truly home-grown.

We often view Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X as having ascended the mountain-top of black achievement and activism. There are several others too. But with the exception of journalist Claudia Jones, also considered the mother of Notting Hill Carnival, few of them appear to have ever lived on these shores.

We often view Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X as having ascended the mountain-top of black achievement and activism. There are several others too. But with the exception of journalist Claudia Jones, also considered the mother of Notting Hill Carnival, few of them appear to have ever lived on these shores.

This is curious as, like those in Africa and the Americas, the UK black community has made large strides forward in terms of civil rights and making a place for themselves in society.

From the resolute battles against racism in this country to the growth of black book shops where you could buy educational material to teach yourself Yoruba, for example, or a card with a black face on it for Mother’s Day – these advancements needed visionary leaders, yet many of their names are forgotten, or worse, unknown.

Documenting and archiving are essential if we are to preserve our history, says Makeda Coaston, a cultural curator. ‘Only a few of us know information about British black history – archives are a way to think more clearly about our history.’

Indeed, it took some 20 years since her death in 1965 for the first biography on Claudia Jones to be written.

With a number of blue heritage plaques to her name, and her face on a commemoration postage stamp among other things, she’s now almost impossible to forget.

Coaston has curated a free exhibition which opened last week at the Guildhall Arts Gallery on Black British Art between 1960 and 1990.

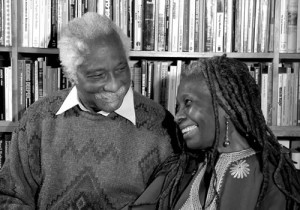

Called No Colour Bar: Black British Art in Action 1960-1990, the exhibition takes its impetus from the life and work of Eric Huntley and his late wife Jessica.

Called No Colour Bar: Black British Art in Action 1960-1990, the exhibition takes its impetus from the life and work of Eric Huntley and his late wife Jessica.

The Guyanese-born cultural and political activists set up the pioneering Bogle-L’Overture publishing house and bookshop in Ealing in 1968, two years after Trinidadian the late John La Rose set up his New Beacon bookshop and press near Finsbury Park.

The exhibition combines art from the period, a modern-day recreation of Bogle-L’Overture bookshop, and some material from the Huntleys’ own archive. The thinking behind combining so much Coaston says is because ‘activism, culture, art don’t each exist in a vacuum’.

The variety of artwork on show forces us to think seriously about what black art is, or whether there is any such thing as ‘black art’ at all.

The exhibition showcases art that looks both familiar: such as Dancing at Reading Hall an oil painting by Paul Dash which depicts a steamy room full of black people gyrating, flinging and catching themselves while wearing in the dapper attire of the day; and the enigmatic: Kaieteurtoo by Royal Academician Frank Bowling named after a famous Guyanese waterfall is a textured acrylic abstract painting with white and red vertical lines which may not be grasped straight away.

Tension

There is also a very visible tension surrounding the exhibition. Its home, the Guildhall, has been the administrative centre of the City of London for hundreds of years and it was here much of the economic policy that steered the British Empire across the seas was driven, where the wealth coming back from the colonies was dished out and whose permanent art collection is the epitome of imperial chic.

This is dealt with head-on: two fierce black women, sculpted elegantly by artist Fowokan, look a marble Edward VII, self-styled Emperor of India straight in the eye; Barclays bank gets a hard time from Eddie Chambers who, on a mixed media board, writes ‘how long you bastards?’ for the support they lent to the apartheid regime in South Africa; while other black art exhibits appear to do war next to permanent collections under themes such as war.

This is dealt with head-on: two fierce black women, sculpted elegantly by artist Fowokan, look a marble Edward VII, self-styled Emperor of India straight in the eye; Barclays bank gets a hard time from Eddie Chambers who, on a mixed media board, writes ‘how long you bastards?’ for the support they lent to the apartheid regime in South Africa; while other black art exhibits appear to do war next to permanent collections under themes such as war.

The Huntley Archives are the first collection of African-Caribbean heritage to be placed at the London Metropolitan Archives. Coaston hopes its inclusion in the exhibition will inspire ordinary people to look at the archives as she says ‘they are a way to think more clearly about our history, learn lessons from history, and ensure it is interpreted in our own eyes’.

Among the material on display from the archives is a letter from Guyanese activist Walter Rodney to Jessica Huntley that has a letter head from the University of Dar es Salaam where he taught, and also the remembrance book signed by attendees at his funeral after he was gunned down in 1980.

Backed by the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), the six-month exhibition combines the efforts of the Friends of the Huntley Archives, The Guildhall Art Gallery and the London Metropolitan archives.

Though funding from HLF took two and a half years to secure, the exhibition would be impossible without its support.

HLF is also behind a number of notable initiatives such as the Staying Power exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum as well as the Black Cultural Archives, which opened in Brixton last year.

This increased urge to preserve Black British culture comes at a time when the British education system is becoming increasingly ossified, while the closing of BBC Three will mean less opportunities for black actors and producers.

To overcome this, Margaret Busby – a friend of the Huntley’s and a publisher in her own right – says ‘we need to continue in the same vein as the Huntley’s: bringing art, publishing and activism together’.

Some see this need as being almost existential. ‘We are at risk of disappearing. There is a tremendous need to direct our energies toward maintaining and preserving our culture,’ says Aggrey Burke, a trustee of the George Padmore Institute in London, which is behind a current exhibition on publisher/activist John La Rose. ‘New generations must find ways to bring the important black figures of Britain forward. We are working against the grain.’

Meanwhile Coaston, American-born though she is, remains dedicated to hoisting British-based activists to the mountain-top of black activism and achievement.

She adds: ‘A lot of black history in schools is about the African-American experiences but there’s plenty in the UK that ought to be showcased. We know about Rosa Parks but not Huntley and La Rose.’

Related links

No Colour Bar: Black British Art in Action 1960-1990